top of page

Getting to Australia 1803

The Ipswich Journal - Saturday 27 June 1801 documents Jonathan’s crime of stealing 3 ewes:

Abberton was in Colchester UK and documents below confirm that is where Jonathan was at the time of his crime. He is listed as a labourer. Colchester is between Chelmsford and Ipswich in the south east part of the UK. It is 50 hours by foot from Wrawby.

Jonathan’s Hulk Register on the Captivity Hulk in 1802 confirms Jonathan Green was sentenced to life on 22nd July 1801 for ‘larceny’ in the Chelmsford Essex assizes. On the hulk is also Thomas Beddow. They were charged on the oath of John Haxell, and on the confession of Henry Hall. Was Henry an accomplice?

The indictment record states:

So Jonathan being the first listed was sentenced to death by hanging commuted eventually to transportation. Thomas Beddow is a repeat offender . This must have been terrifying for Jonathan who was only 25 years old , married and a father to our Frances.

On 28th July Chelmsford “Our Assizes ended on Saturday last, when the following prisoners were capitally convicted, and received sentence of death, viz. ...Thomas Weston, Jonathan Green, Thomas Beddow, and John Howells, for stealing three ewe sheep, the property of Mrs. Canning...Nine of the culprits...were ordered for execution, and the rest were reprieved.” Jonathan was clearly one of the few who were reprieved.

“Far from being the final word in a convict’s fate, the passing of sentence was but an early step in a long and twisting journey with few guarantees of a new life in the colonies. From the courtroom a convict might endure years of incarceration at home before being selected for a voyage…Not every convict sentenced to transportation…arrived in Australia… In its earliest years transportation to Australia was often portrayed as the fate that awaited the worst and most wretched of criminals….Offenders convicted of property crimes made up by far the biggest proportion of those sentenced to be transported. Theft was the largest category of all property crimes…. Grand larceny was a felony charge used in cases of theft over the value of a shilling. Not only did a conviction for grand larceny warrant a sentence of transportation, it could also carry a sentence of death…”[1]

On 10th August Jonathan and John Howell come before the court on stealing the 3 ewes. Thomas Beddows was convicted of a different stealing offence. He stole sheep from Daniel Dyson with a few other men. This had been recognised on the original indictment.

On 27th August 1801 Jonathan was removed to Portsmouth on the hulk Laurel . John Howell aged 31 and Thomas Beddows aged 24 yrs joined him. John died aged 31 yrs on 25th October 1801. He only survived 59 days on the hulk. It is interesting to note that of the men convicted on 22nd July at the same trial as Jonathan, 4 died including John. The others were-

-

William Mofs aged 25 died on 17th Nov 1801. He had been convicted with Thomas Beddows

-

Richard Taylor aged 31 years died on 11th October 1801

-

Thomas Scribner aged 35 yrs died on 14th January 1802

One man escaped on 2nd Dec 1801 Thomas Williams aka George Scott. I hope he evaded capture again. The remaining 13 men with Jonathan and Thomas all were placed on the hulk Laurel. They had all been sentenced to life. William Easmin who had been convicted with Thomas Beddows was one of these 13.

The hulk registers state on 20th Nov 1801 Jonathan and Thomas were either on the Coromandel,. Perseus or Laurel but against their names is the ship Lyon which a reference cannot be found. The Coromandel and Perseus were in fact convict ships that sailed on January, 1802. Arrived 14th August, 1802 at New South Wales. This pre dated Jonathan’s sentencing.

Williams goes on to describe the hulks “ ..one of the most iconic features of the Australian transportation era, England’s dreaded floating prison ships, the hulks, were the plight of male prisoners….When the American war of independence stopped the easy flow of convicts out of Britain, it caused a crisis in the ancient and creaking prison system…. The idea of using decommissioned naval and colonial vessels as ‘overspill’ incarceration was made law by an Act of Parliament in 1779..Beatrice and Sydney Webb wrote in their 1922 history of the British prison system:

Of all the places of confinement that British history records, the Hulks were apparently the most brutalizing, the most demoralizing and the most horrible,. The death rate was appalling, even for the prison of the period”.[2]

The Hulk Laurel Ref: https://sites.google.com/site/richardwoodbury1777/prison-hulk

The Laurel was the Dutch ship "Sirene", captured at the Battle of Saldanha Bay in South Africa in 1796. It was renamed HMS Daphne before being made a prison ship at Portsmouth in 1798. It remained in service there for some 28 years. Typically, prison hulks had masts, rigging and rudders removed. Guards lived in barracks built on deck. Dock-side ports (windows) were usually secured shut to prevent escape by the prisoners, but this only exacerbated poor ventilation and subsequent disease on board. Prison diets were often poor consisting mainly of ox-cheek, salted meat, oatmeal, bread or biscuit. Water was drawn from the river so dysentery was common.

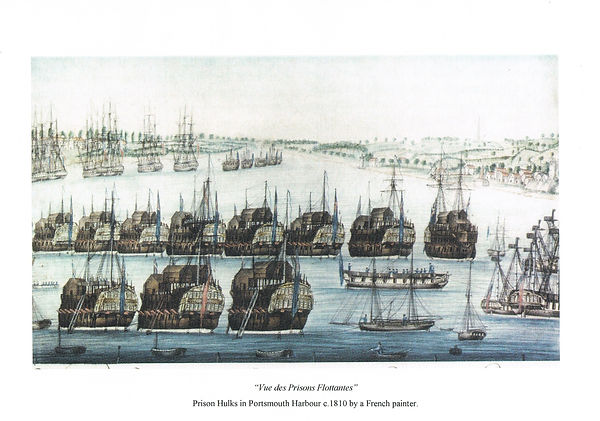

Images of the prison ship HMS Laurel in Portsmouth harbour have not been found. However, images of similar vessels are available. HMS York (pictured) served as a prison hulk in London and Gosport (Portsmouth) between 1820 and 1852. HMS York was 175 feet in length and usually held about 500 prisoners. HMS Laurel was 118 feet in length and held about 200 prisoners.

Prison hulks were acknowledged even at the time as places of appalling misery and disease. As the National Maritime Museum indicates, "during the first 20 years of their establishment (from about 1776) the hulks received around 8000 convicts. Almost one in four of these died on board. Hulk fever, a form of typhus that flourished in dirty crowded conditions, was rife, as was pulmonary tuberculosis” [National Maritime Museum, London, in Portcities.org.uk].

In 1807, Neild, found that there was "allotted to the Laurel on the Gosport side of Portsmouth, a plot of ground about 100 feet square which produced cabbages and other garden-stuff sufficient to supply every convict with vegetables, one, two and sometimes three days in the week”. Also the Surgeon “visits the ship once or twice a week”. Richard’s [ author’s ancestor] transfer to Laurel may have been a piece of luck, given that the diet for inmates at Newgate prison in Bristol was known to be poor, consisting mainly of a daily allowance of bread. It may be that the superior vegetable diet on board the Laurel improved Richard's health sufficiently for him and his fellow convicts to survive the long sea voyage to New South Wales. Also, there was active work available at Portsmouth, which was not permitted in any form at Newgate.

It is quite possible that these better conditions were present when Jonathan and Thomas were on the Laurel. This is what Portsmouth looked like in 1810 long after Jonathan left but it gives some idea of the Hulks

The Hulk Captivity: https://www.ourfamilypast.com/article/topic/8145/haa007-breakout1-prison-hulk-captivity

The prison hulk Captivity started her life as the seventy-four-gun warship Bellerophon.

Born 7 October 1786 in the Medway River, Sussex England, the Bellerophon was nick-named Billy Ruffian by her crew. At the tender age of just eight years old Billy Ruffian was involved in her first major clash; the battle of the Glorious First of June 1794 against the French. The battle was a British victory, but only just.

Four years later Billy Ruffian was again engaged in another encounter against the French in the battle of the Nile 1798. This mêlée stranded Napoleon in Egypt with his troops.

Bellerophon was involved in the battle of Trafalgar in 1805, a crushing victory for Britain against France which ended Napoleon’s plans to invade Britain. Napoleon was finally defeated in the battle of Waterloo 1815 and fled from France. Soon afterwards he surrendered himself to the Captain of Billy Ruffian; Frederick Maitland.

Like many other ships and soldiers at the end of the Napoleonic conflicts, there was no further use for them. But Billy Ruffian had a second life as a prison hulk. She was stripped of her guns and masts and re-fitted with cells for the prisoners.

Bellerophon served as a hulk in the same River she made her debut in nine years earlier. In 1824 she was renamed Captivity and moved to Devonport where she continued as a prison hulk for another ten years.

In 1834 all of her prisoners were either removed to their transportation ships or relocated to the Leviathan hulk (who was also present at the battle of Trafalgar) and the Captivity was used as a hulk exclusively for adolescent boys.

In 1836 Captivity was sold and broken up; dismantled for scrap wood.

On 17th January 1802 Jonathan is on the hulk Captivity still with Thomas Beddows aged 24 yrs See below. They were transferred to the Glatton on 8th September 1802 for their voyage to Sydney and penal servitude. The Glatton was only one of 4 convict ships sailing that year and had 154 men with life sentences and 402 passengers. The average sentence of the convicts was in fact only 8 years. https://convictrecords.com.au/timeline/1802

There is some confusion here also- he could have been on the Portland at some time also:

Report of convicts under sentence of transportation removed from sundry Gaols by command of his Majesty on Board the Portland Hulk, Langston Harbour, commencing 1st January 1802. No. 469. Jonathan Green Age 26. Convicted: 22 July 1801: Sentence: N.S.W. Life; Vessel: Glatton.[3]

Perhaps he was moved from Captivity to Portland to Glatton or ancestry has the hulk Captivity wrongly cited.

Williams describes the journey of convicts post sentence as a bit of a lottery. Not all would come to Australia although young men like Jonathan if he was healthy were a priority as they were needed in the new colony. There was a process of selection which was described by Henry Capper, His Majesty’s Superintendent of the Hulks in an parliamentary select committee in 1812:

When the hulks are full up to their establishment, and the convicted offenders in the different counties are beginning too accumulate, a vessel is taken up for the purpose of conveying part of them to New South Wales. A selection is in the first instance made of all the male convicts under the age of 50, who are sentenced to transportation for life and for 14 years; and the number is filled up with such from amongst those sentenced to transportation for 7 years, as they are the most unruly in the hulks, or are convicted of the most atrocious crimes; with respect to female convicts, it has been customary to send, without any exception, all whose state of health will admit it and whose age does not exceed 45 years”[4]

Williams’ notes that to stand a good chance of being transported convicts needed to be young enough to be useful in the colony, robust and healthy enough to withstand the arduous trip out and the colony itself on arrival. Jonathan fitted this profile. Luckily Jonathan only spent 5 months on the hulks before he was transported so stood a good chance of survival. What though of taking Elizabeth and baby Frances on the ship with him? How frightening that must have been for Elizabeth.

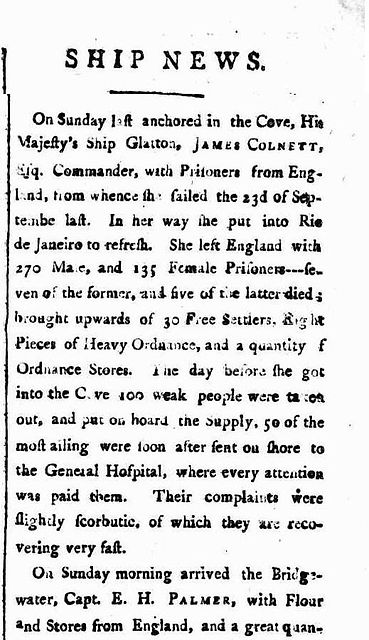

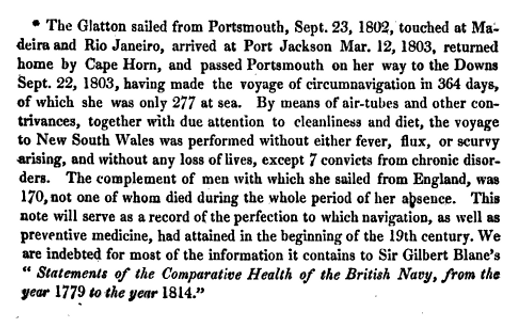

The Glatton [below] left England on 23rd September 1802 and arrived in Sydney on 11th March 1803 having sailed via Madeira and Rio De Janeiro . The voyage took 169 days and had 12 deaths. It contained 270 male convicts of whom 7 died on voyage [one being Thomas Littlejohn], 135 female convicts of whom 5 died on board and 30 passengers.[5] We don’t know if Elizabeth and the children would have been counted as passengers. The children are unlikely to have been. Frances would have been 6 years of age and her brother Jonathan Cooper Green 3 years of age. Jonathan Cooper had been baptised in April 1800 in Surrey. The Glatton had been previously commanded by Captain William Bligh, it took part in the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801.[6]

Drawings below of The Glatton courtesy of the National Maritime Museum UK. Click on maps to go to the online drawing.

A relative of Thomas Littlejohn describes the journey leaving England:

In September 1802 around 400 other male and female convicts were transferred to HMS Glatton, at Portsmouth, under Captain Colnett. On board were also 30 paying passengers. The ship set sail at 4pm on the 23rd September in light breezes and fair weather. For many on board, when they saw the Lizard on the Cornish Peninsular next day, it would be the last time they would ever see England. They arrived at Port Jackson (Sydney) on March 13th 1803. Mr Colnett was an enlightened commander for his day and far fewer convicts died on the journey (12) than previous voyages. Nevertheless 100 of them had to be hospitalised on their arrival. Although the ship had men's and women's prisons, it seems that prisoners were not confined to them all the time and were given work to do. They were even allowed to carry their knives. Security was a concern for the captain, during the voyage he had the ship's carpenters build scuttles on deck for the officers to communicate with each other should the prisoners attack. Discipline was harsh and several crew and prisoners were flogged for things like theft and other infractions of the rules.[7]

Thomas died on 14 February 1802, onboard “Glatton” on the outward voyage (HMS Glatton, Captain's Log 1801-2 (PRO ADM 51/1467).

The Glatton was reported in May 1802 to be fitting up at Chatham to carry convicts to Botany Bay and bring back masts and the Admiralty produced a set of instructions for Captain James Colnett:

Whereas we have thought fit that the ship you command shall be employed on that service, you are, in pursuance of H.M. pleasure signified as above mentioned, so soon as the convicts whom you have been ordered to receive shall be embarked, and the said ship in all respects be ready, hereby required and directed to put to sea and proceed in her to Port Jackson, in the said colony of NSW accordingly calling in your way thither at such place or places as you may judge most convenient and proper for the purpose of obtaining refreshment.

You are to victual the convicts during their continuance on board in the same manner as convicts are usually victualled and on your arrival at Port Jackson to deliver all the said convicts which may then be with you into the charge of the Governor. You are to be very careful to keep a sufficient guard upon the said convicts during the time they may remain on board the ship you command, so as to prevent the execution of any improper designs which they may form; and in case it should be requisite on your passage to New South Wales to provide necessaries for them at any port at which you may stop, you are to purchase such necessaries, if they can be procured, and to draw upon te Lords Comm'rs of H.J. Treasury for the amount thereof.

And whereas the Governor of NSW has been instructed to cause a quantity of timber proper for H.M. service to be cut down and prepared in order to be sent to England for the use of H.M. Dockyards, you are hereby further required and directed to receive on board the ship you command such quantities of the said timber as well as any other produce of the said colony that may be judged proper to be sent Home as you can conveniently stow. (Admiralty to Captain James Colnett 2 September 1802. [3]) https://www.freesettlerorfelon.com/convict_ship_Glatton_1803.htm

Correspondence from Lord Pelham to the Treasury on clothing to be provided on the Glatton

Lord Pelham to the Treasury

My Lords,

Whitehall,

12th May, 1802

It being judged expedient to send forthwith from this country four hundred convicts to New South Wales, I am to desire that your Lordships will be pleased to cause the necessary directions to be given to the Victualling Board for providing a sufficient and proper quantity of provisions for their subsistence during the voyage, and salted beef or pork only for nine months for them after their arrival at New South Wales. I am also to desire that your Lordships will cause the necessary directions to be given for providing the 270 male convicts the particulars of cloathing as undermentioned, to be consigned to the Governor for the use of such convicts on their arrival at that settlement, and that the said provisions and cloathing may be put on board His Majesty's ship Glatton, which is now fitting at Sheerness for the conveyance of those convicts. It being also intended to allow about forty persons to embark on board the said ship who are going as settlers to that colony, I am to desire that directions may be given for providing the usual quantity of provisions for such number during their voyage thither. ............ 1 blue jacket or waistcoat, 1 p'r Russian duck trowsers, 3 checked shirts ,2 pairs of stockings, 1 pair of shoes, 1 woollen cap [1]

Utensils for brewing and hops were also sent on the Glatton. A brewery was later set up at Parramatta...........

Historical Records of Australia Series 1., Vol IV., p 460

{Extract}

Governor King to Lord Hobart

Sydney New South Wales

March 1st 1804

Respecting the utensils for brewing, and the hops sent by the Glatton and Cato, I have a pleasure in saying that the former are all fixed at Parramatta in a building appropriated for that purpose, with a kiln and every other requisite for malting barley and brewing under the same roof. 142 pounds of hops were bartered with a settler who has long brewed in small quantities.

The remainder I shall preserve for the purpose of brewing for the use of those your Lordship points out, which has always been an event much desired by me. A trial has been made in which we have succeeded in making a small quantity to begin with, and I do not doubt but we shall soon carry it on in a very large scale. That which is made is very good, altho' we have no one proficient in brewing to conduct it. In a former letter I stated what might be expected from the utensils for brewing and the hops sent by the Glatton, and that the indifferent kind of barley we possessed would enable us to continue brewing beer when commenced; nor do I doubt but your Lordship's attention to this colony will direct my request being granted for some good seed barley and more hops being sent, also another set of brewing utensils for Sydney and one for Norfolk Island.

It would also be a future benefit if a thousand well established hop plants could be put on board any whaler coming direct.. There are now about forty thriving hop plants growing from a quantity of seed brought by an officer in 1802 which are much taken care of .

https://www.freesettlerorfelon.com/convict_ship_Glatton_1803.htm

The arrival of H.M.S. Glatton in Sydney Cove on 11 - 12 March 1803 was reported in the Sydney Gazette:

In her way the Glatton put into Rio de Janeiro to refresh. She left England with 270 Male, and 135 Female Prisoners-seven of the former, and five of the latter died; She also brought upwards of 30 Free Settlers, Eight Pieces of Heavy Ordnance, and a quantity of Ordnance Stores. The day before she got into the Cove 100 weak people were taken out, and put on board the Supply, 50 of the most ailing were soon after sent on shore to the General Hospital, where every attention was paid them. Their complaints were slightly scorbutic, of which they are recovering very fast. - [4] https://www.freesettlerorfelon.com/convict_ship_Glatton_1803.htm

Elizabeth and her children were not cited on the records of the Glatton.

It appears Captain James Colnett of the Glatton got himself into a bit of uproar on arrival given his “ friendship” with a convict woman onboard who had provided “ special services” during the voyage!! A recounting of this in 1933 tells the story that Colnett was somewhat involved in the downfall of King:

A GOVERNORS WORRY- A First-class Row : Captain Colnett, His Convict Lady-friend, and Governor King. By "MAKAIRA"

In the early afternoon of March 11, 1803, H. M. Ship Glatton

(Captain James Colnett) entered Sydney Heads,

168 days out from England, with 400 convicts and

a large consignment of stores and supplies for the

settlement. Captain Colnett arrived fully prepared,

should the occasion arise, to disapprove strongly of

everything about Sydney. It did arise, as will hereafter

be related, and in a communication, five months later,

to Sir Evan Nepean, Secretary to the Admiralty,

he described the famous Harbour as having a dangerous

shoal in the entrance, with a narrow, wind-ing channel,

no deeper than four fathoms at high water, and no wider

than the ship. "A ship," he wrote, "is obliged to wait for

the tide to carry her over the barr. ..."

Young Sydney he compared to "a miserable Portuguese

settlement." Nor was he satisfied, as a senior Naval Officer,

with his reception. Only one of the commanding officers

of the two navy vessels on local station called on him,

and that was "on his own business, not the service's,

having two rams brought for him."

Painting of Sydney in 1803 from the west side of the cove.

Artist: George Evans 1802. Click on painting to go to website

Captain Colnett's Protege.

ONCE in personal touch with the busy and harassed Governor Colnett seems to have been treated with every courtesy and consideration. Administrative affairs were very disturbed and troublesome. Major Johnston, temporary O.C. of that extraordinarily drunken and unsoldierly force, the New South Wales Corps (in local parlance, the Rum Corps), was practically defying the Governor's authority. The O.C.. Lieut.-Colonel Paterson, a suave and untrustworthy gentleman, was "indisposed." It was his habit to be so when-ever anything unpleasant occurred. Sir Henry Hayes, that picturesque yet pestilential convict baronet, was kick-ing up a deal of trouble; annoying and malicious lampoons against King were being circulated: and the weight of the Tasmanian settlement was on his shoulders. Into this rush of worrisome affairs, Captain Colnett intruded the modest request that "an unfortunate young woman" who had come out at a convict in his ship should receive a free pardon, and be allowed to return in the Glatton. "This is a duty I owe her," he wrote to King, "for the secret services she rendered me relating to the convicts, &c &c, during the passage." King replied regretting that, in spite of the lady's "secret services, &c, &c," his official instructions specifically forbade him to do any such thing. "As I candidly explained to you two days ago," his letter proceeds, "granting a free par-don to a person who has not been resident here 12 months is what I dare not do without subjecting myself to ruin. . . ." He offered a conditional emancipation two months later as the best that could be done, but the girl must remain in the colony.

A Paper War.

"FINDING the Governor firm, Colnett dropped the mask and proceeded to make himself as unpleasant as possible. An opportunity arose when a young man named Whittle, who had gone aboard the Glatton, and made' some impudent remark to Midship-man Walpole, was ropes-ended over the side by Lieutentant Stewart. Now, this Whittle was a son of a pugnacious sergeant of the Rum Corps, and on parade next day the indignant parent expressed, publicly and abusively, his opinion of Lieutenant Stewart, winding up with a threat to cut his ears off whenever he met him. Colnett demanded the court-martialling of Sergeant Whittle. King replied that the case was one for a civil or criminal Court. Colnett dragged in side issues on King's lack of sincerity in his letters and actions, and a royal row was on.

Colnett got in some dirty work over the alleged unfitness for shipbuilding of certain timber sent down for loading; accused King of deliberately d-laying the ship's departure, and of keeping her short of supplies. There was a terrific uproar when a quantity of spirits, which Colnett had apparently brought out as a private venture in partnership with Mr. Campbell, of Syd-ney, was seized as it was being put ashore quietly. Added to the bruised heart suffered already over the matter of the lady convict, this stab in the pocket was beyond Colnett's powers of bearing. In an impassioned outburst to the Secretary of the Navy he accused King of having "in a clandestine manner procured 84 gallons of spirits, . . . made a catspaw of me, and deceived the garrison ... he felt no repugnance in causing a sick man's grog to be seized."

Mr. Chapman's Offer.

NEEDLESS to say Mr. W. N. Chapman, the Governor's Secretary, was well acquainted with the whole affair. On May 13 Mr. Chapman spent the evening with Captain Bowen and Surgeon Mountgarret at their bachelor establishment. Midshipman William Pitt (the Glatton seemed to attract "snotties" with famous political names) and the Master's Mate were also guests. These two youngsters tattled to the Captain that they had heard Chapman say that the Glatton would not sail for a fortnight. Next day Colnett wrote to King accusing Chapman of having "publicly declared that I am not to go to sea this fortnight." King replied that he had dismissed Chapman from his position "until he proves or disproves the direct lie he has given to the assertion you make use of," and added a nasty one to the effect that any delay would give the Glatton's purser time to "settle his long-delayed accounts with the Commissary." He also enclosed Mr. Chapman's denial, which was even less calculated to please Colnett. It ended: "I hereby declare that Captain Colnett or any other person who dares to say that I ever gave it out . . . is a liar, a scoundrell (sic), and a vagabond; and that whoever he is, if he has the spirit to come forward, that I will wring his nose and spit in his face."

A Peaceable Ship's Company.

THESE were duelling days, but Mr. Chapman's handsome offer did not attract any fire-eater from the Glatton. Colnett demanded a Court Martial or Criminal Court. Chapman gave notice of action against Colnett for £10,000 damages. King offered a civil trial if Colnett would attend it. If Colnett did not he would reinstate Chapman. Colnett did not - probably wisely - and Chapman was reinstated.

On the voyage Home Colnett composed a letter to the Admiralty concerning King and his misdeeds, which leaves even that justly celebrated ecclesiastical curse which devastated the Jackdaw of Rheims far behind. Unluckily he had powerful friends: Lord Hobart wrote King that he would be relieved as soon as there was selected "Some person free from the spirit of party which has reached such an alarming height."

And the joke was that the person selected as free from party spirit was, of all people, Captain "Breadfruit" Bligh, already famous in two hemispheres as the very embodiment of arrogant pugnacity and mandriving martinetship.[8]

In this article are references to men closely aligned with our Josephus Henry Barsden, of course Governor King but Surgeon Mountgarrett and Paterson who is described here in very different terms to what we see in Josephus’s diary. Refer to the Barsden chapter for more information. Jacob Mountgarrett was the surgeon on the Glatton! No surgeons diary exists for the ship but Colnett write a diary of this voyage.

[1] Williams Lucy, Convicts in the Colonies: Transportation Tales from Britain to Australia. Pen & Sword Books 2018 page 1-3.

[2] Williams Lucy, Convicts in the Colonies: Transportation Tales from Britain to Australia. Pen & Sword Books 2018 page 20-22.

[3] https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/168009969/person/332182775081/story

[4] Op cit page 33.

[5] https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Space:Glatton%2C_Arrived_11_March_1803 https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/glatton/1802

[6] https://dictionaryofsydney.org/artefact/hms_glatton

[7] Symonds Trish https://www.opc-cornwall.org/Resc/emigrant_pdfs/littlejohn_thomas_1802.pdf

[8] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 - 1933), Saturday 24 June 1933, page 20

bottom of page